Re-developing West Kentish Town:

Courtyard housing & good urbanisation, article by Tom Young

Good growth across London requires development to optimise site capacity, rather than maximising density, GLA, with Mae Architects, Optimising Site Capacity: A Design-Led Approach (2023).

.

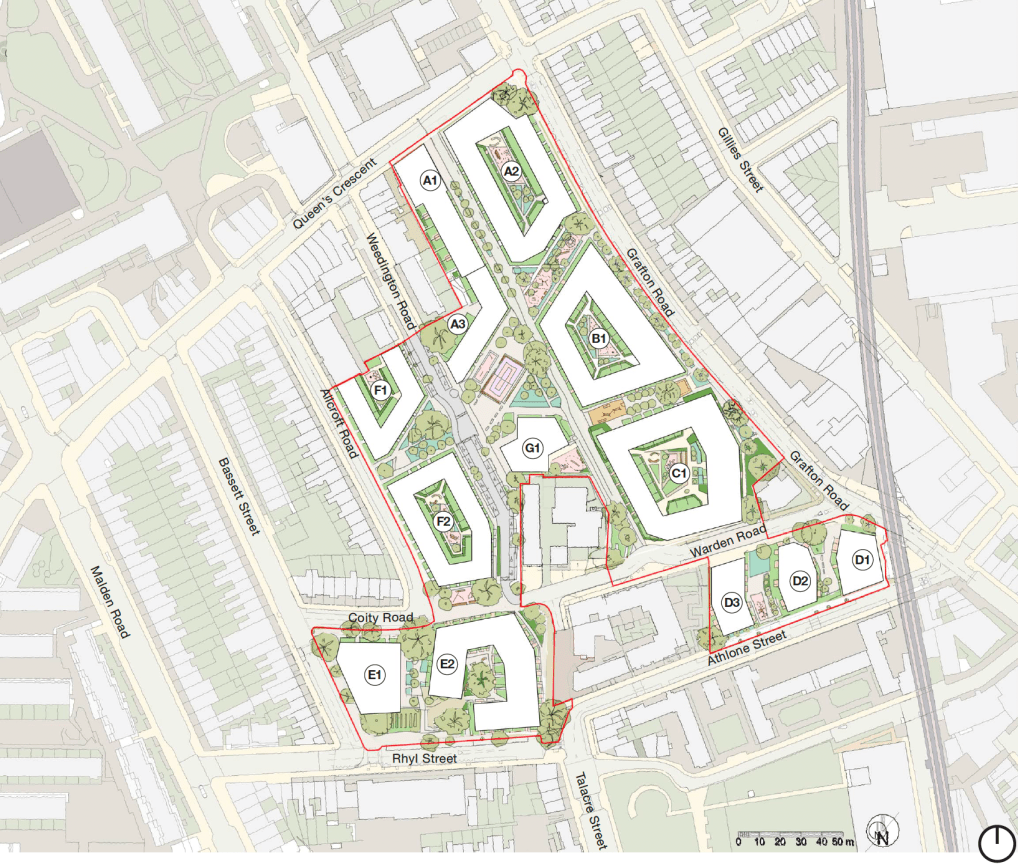

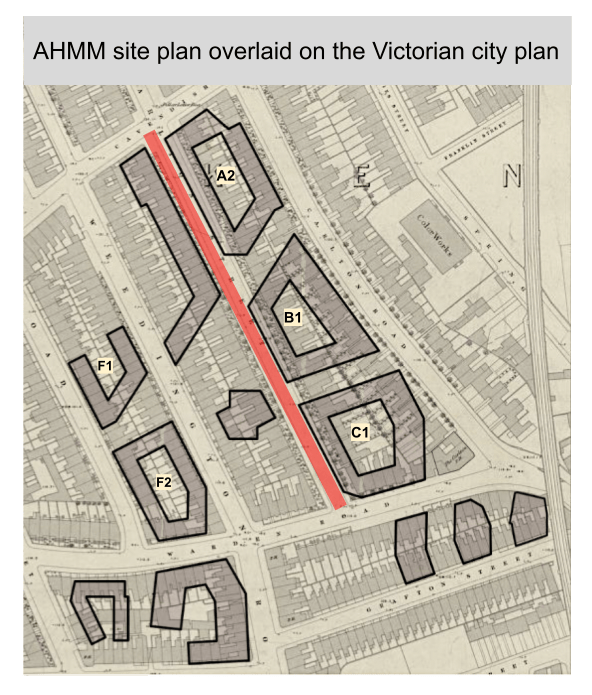

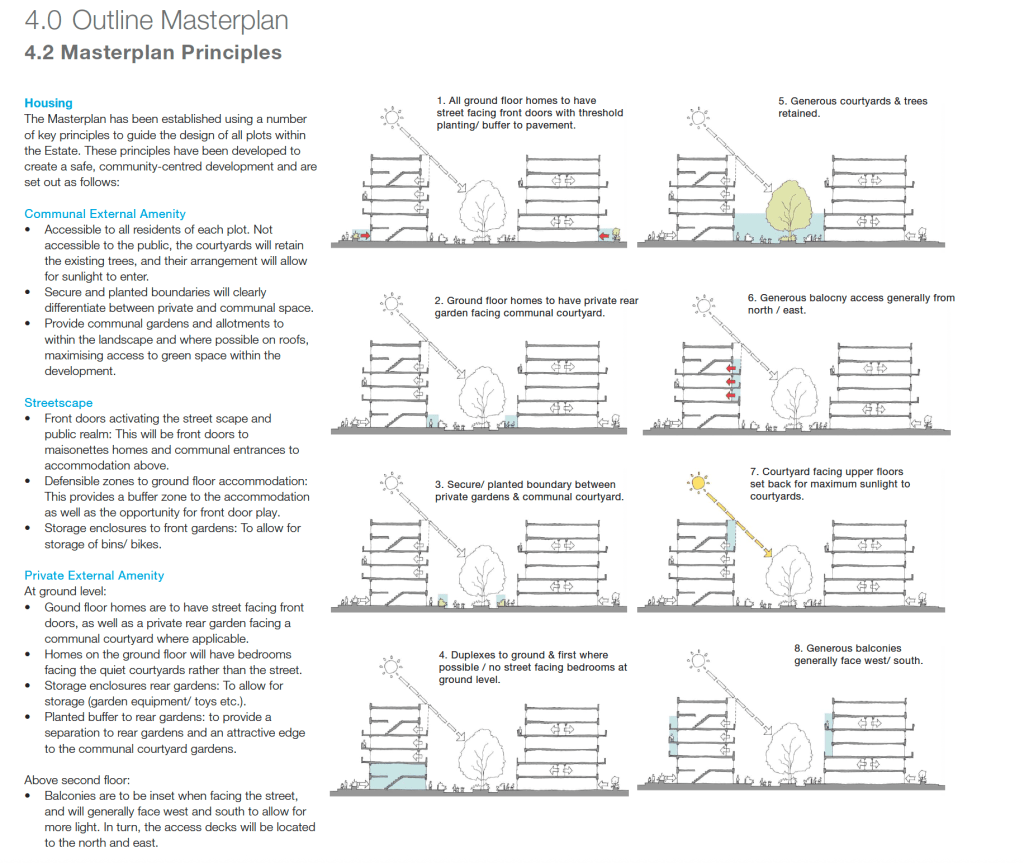

The West Kentish Town Estate (WKTE) redevelopment, led by AHMM Architects, has 12 building plots. Seven will be courtyard buildings containing over 70% of the 856 new homes planned (around 600 in total). They are not in the first phase of work so detailed designs are not yet available. The plots on which they will stand, their maximum size plus other general information is shown in the parameter plans, while the design documents (DD) i.e. the Design Code (DC), the Design and Access Statement (DAS) and Planning Statement (PS) fill in some of the rest of the missing information. The following is a discussion of the proposed courtyard housing based on what is now known about it.

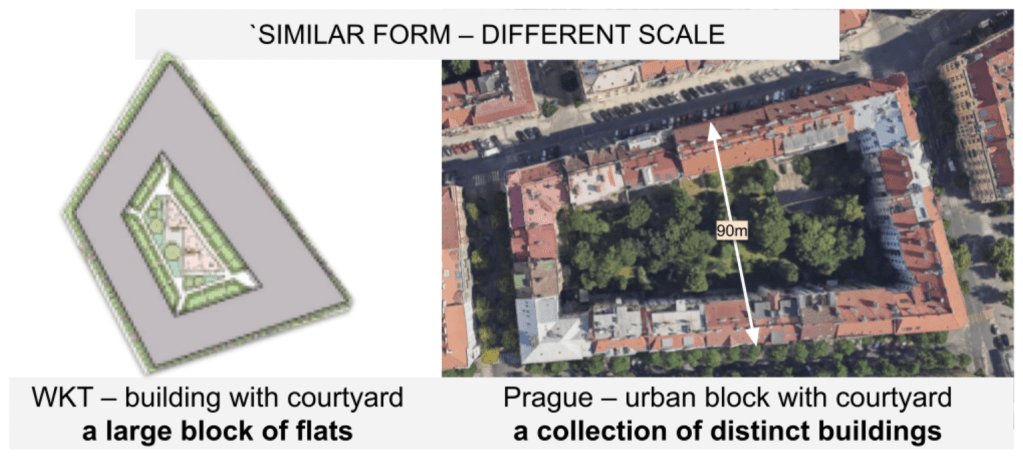

COURTYARD BUILDING OR PERIMETER BLOCK?

The DD argue that courtyard buildings are a suitable ‘typology’ for the WKTE redevelopment: “Courtyard buildings are a prevalent building typology in Camden, exemplified by nearby mid-century developments, like St John’s Court and Denton Estate. These buildings define the Estate’s perimeter, creating recognizable streetscapes and architectural variety. The internal courtyards serve as shared amenity spaces, fostering community among residents.”

While there are countless examples of building groups that enclose an inner area, they are perimeter blocks not courtyard buildings. Genuine courtyard buildings are scarce in our neighbourhood. In Gospel Oak and most parts of London, perimeter blocks are a norm, often taking the form of 19thC terraced housing which the WKTE comprehensive redevelopment is surrounded by.

above: typical perimeter block in Primrose Hill

Terraced housing is the best known and most commonplace system for assembling buildings (terraces) from individual dwellings (houses) on city blocks defined by streets or public space. What the DD authors call ‘typologies’ are ways of assembling dwellings (flats or houses) into buildings that fit on urban sites usually defined by streets. A great deal of inventiveness has been applied to the dwelling/building/city-block pattern in the last 200 years as urbanism has become central to modernity. Gospel Oak includes some of it e.g. at Dumboyne Estate, the New Harmood Estate and in Benson & Forsyth’s projects.

Mae Architects have worked on WKTE’s redevelopment for well over 10 years and remain actively involved. In 2023, they contributed to the Mayor of London’s planning guidance (LPG) Optimising Site Capacity: a Design-Led Approach, which uses West Kentish Town Estate as a case study. It proposes stereotypes labelled ‘the terrace’, ‘linear block’, ‘the villa block’ and ‘the tower’ to measure site housing capacity in relation to one of three densification and town-planning scenarios labelled ‘conserve, enhance or transform’:

The use of generic residential building types is meant to show housing capacity evaluation has been integrated with architectural form at an early stage – that is to say, architectural thinking has not been overwhelmed by ‘a numbers game’:

“The whole big conceptual aspect that goes with housing need … as far as I can see, has been overtaken, again, simply, by a numerical view about what the building industry can do with certain advantages given to it by government. That’s not what I consider to be the way to approach a housing programme”

Neave Brown, Building for the Boroughs: Neave Brown and Paul Karakusevic in conversation, July 2015.

The LPG sets out a sequence of seven steps to model site capacity: only at the sixth is site capacity even mentioned: “Once satisfied with the design option produced, the residential GEA can be taken from the modelled scheme and used to identify indicative site capacity based on tenure and type mixes.“

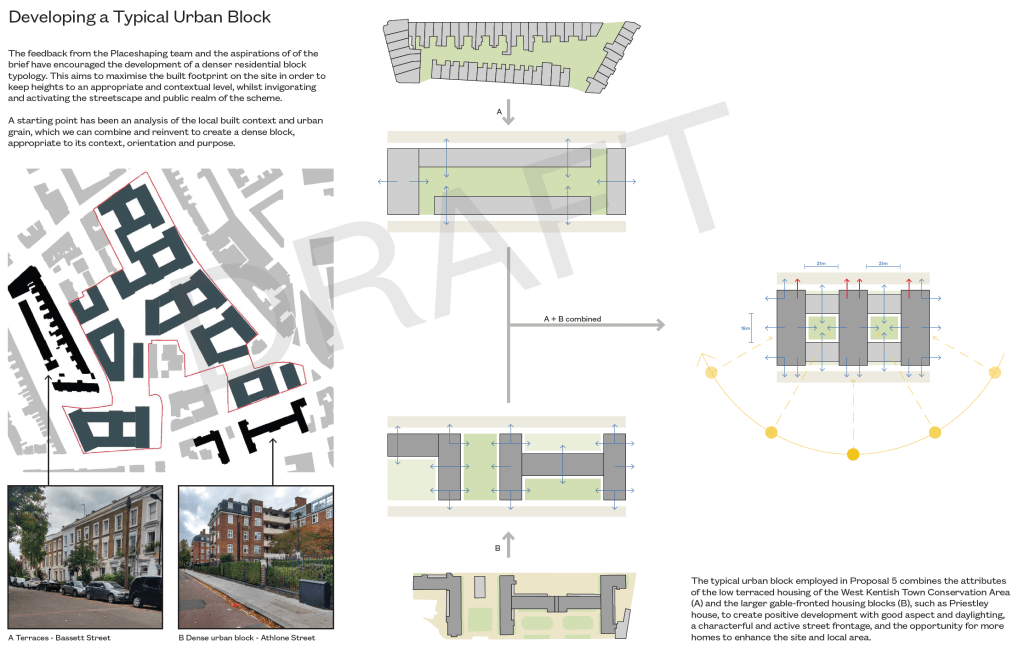

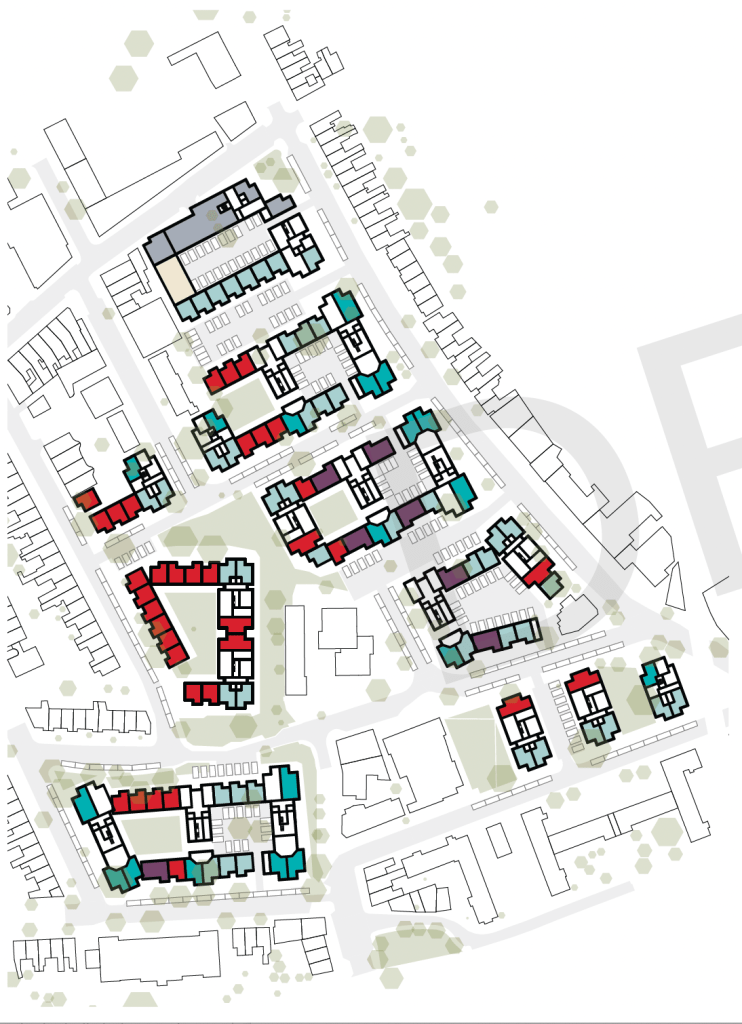

Mae’s early work for Camden on the housing capacity of the WKTE site (West Kentish Town Feasibility Report (Final Draft), 2017) preceded the LPG by a few years and took a different approach. Instead of architectural stereotypes, it explored site capacity via a custom-made dwelling/building/city-block pattern:

which is laid out in a preferred site plan option called Proposal 5:

“The typical urban block employed in Proposal 5 combines the attributes of the low terraced housing of the West Kentish Town Conservation Area and the large gable-fronted housing blocks e.g. Priestley House, to create positive development with good aspect and daylighting, a characterful and active street frontage, and the opportunity for more homes to enhance the site and local area”

This new typology hints at renewing disinterested work on the dwelling/building/city-block pattern which figures like Peter Tábori and Neave Brown are famous for. It could have led to a sensible site development proposal for WKTE especially since the cited Bassett Street and Athlone Street precedents for Mae’s new pattern are three and five storey buildings respectively. But Proposal 5 has many tall buildings up to 15 storeys and near enough all the blocks are higher than the precedents. In other words, although the layout is quite good, and offers hope of sensible urbanisation, it is mangled by its authors to demonstrate the scope for trebling site density from 316 to 902 homes.

TRAD LOOK

AHMM’s and Mae are working together on the WKTE redevelopment and seem to share a commitment to ‘recognizable’ type-based approaches to site development informed by regard for the historic city. See the PS’s call to “Reinstate the historic streets … and create traditional streets” and the statement that “Courtyard buildings are a prevalent building typology in Camden…creating recognizable streetscapes and architectural variety”. Mae remarked in the 2020 draft LPG about potential for “Courtyard-forming blocks or perimeter blocks (that) characterise much of historic London…(offering) a continuation of the grain of London’s streets, legibility”. Important lessons are thus identified with historic London while the existing estate’s Modernist approach is presented as failure in the PS:

“Built form within the Site is unremarkable and of no particular architectural quality. There is a lack of relationship between the buildings within the Site and the surrounding townscape in terms of layout, form, style and materiality, leaving the Site experienced as a contrasting ‘island’ within the wider townscape“

AHMM’s proposed seven courtyard blocks are all irregular in plan, each different to the others, partly as a result of the new network of public spaces which delimits the buildings and partly, as we are led to believe, because of nuanced urban design responses to surrounding ‘character areas’:

above: permitted masterplan for WKTE by AHMM

The courtyard figures want to be read as complete urban blocks but are simply not big enough, which becomes apparent by comparing them to nearby 19thC ones e.g. the one formed by Bassett Street and Malden Road.

Panerai noted a comparable issue with Hausmann’s urbanisation in Paris:“…because of the very heavy densification to maximise the profitability of the ground … the plots became so diminutive in relation to the building types” (Philippe Panerai, Urban Forms: Death and Life of the Urban Block 1977).

The eccentric shape of AHMM’s courtyard buildings may be like that of older perimeter blocks but nothing else is. The accommodating properties of traditional urban blocks (e.g. adaptability, partial replaceability, non-residential uses) are missing. Learning from the past or renewing tradition is difficult.

And AHMM’s proposals do lack precedent. The Daylight, Sunlight and Overshadowing report states “There is little precedent of a masterplan scheme of this scale that includes courtyards within Camden” which argues for more information from the designers about their choices. That would be a start. Complementary to it would be some insight into the works of past masters with relevance to the site layout which AHMM are architecturally committed to.

Mentions of ‘typologies’ demonstrated at Denton Estate, St John’s Court, the Dunboyne Estate, the Weedington Estate and Agar Grove Estate are scattered across the planning documents without an explanation of their direct relevance to the WKTE courtyard proposals.

SITE

AHMM’s site planning for WKTE is defined by a new north-south spine road. The move is vouched safe by Mae’s preliminary work which observes that “Historically the site was concentrated on a strong north/south orientation, due to the traditional Victorian terraced street typology”. The PS supports the aim to “Reinstate the historic streets where appropriate to improve movement and create traditional streets (and) Celebrate the history and heritage of West Kentish Town and connect it to the conservation areas around”. The DC talks about the AHMM layout as an “accessible urban grain (that) prioritises pedestrian access and facilitates appropriate movement across the Site”. This “appropriate movement across the site” is enabled by quasi-streets called “public pocket space” that “connect to the conservation areas around”.

It is a lot simpler to think that the job of the ‘public pocket spaces’ is to break up the eastern flank of the AHMM layout into three courtyard-type blocks of flats (A2,B1,C1) to create more frontage and density.

Mae’s 2017 layout shows that the spine wasn’t always important. The current notion that there is a need to ‘reinstate’ the ‘north/south orientation’ or ‘the traditional Victorian terraced street typology’ is conservation blah-blah to give respectability to poor town-planning. AHMM are reintroducing the spine to get more flats in, ignoring the fact their courtyard buildings do not sit well on the squashed parcel lying between it and Grafton Road.

EFFICIENCY

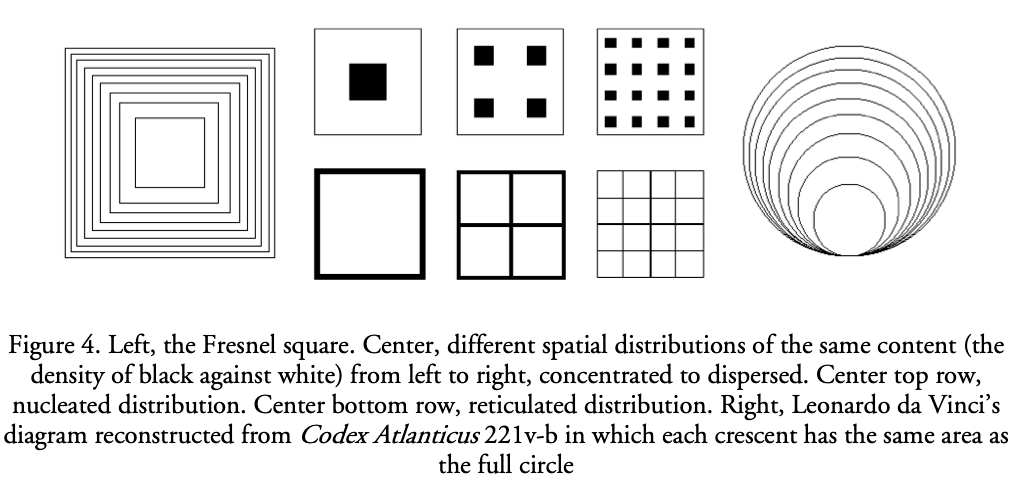

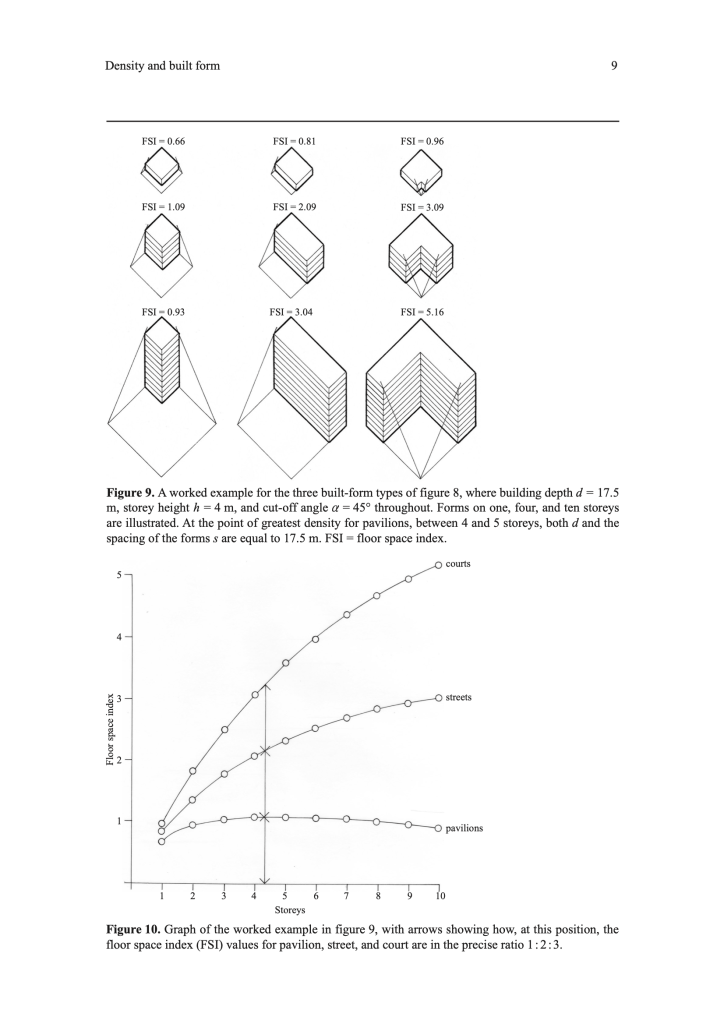

In the Sixties and Seventies, Lionel March and Leslie Martin wrote a series of well-known papers about efficient urban planning which explored the courtyard or perimeter block. They noted that floor area in a notional multi-storey tower could be re-configured in a perimeter block and “so arranged would pose totally different questions of access, of how the free space is distributed … and what natural lighting and view the rooms within them might have” (Lionel March & Leslie Martin, Urban Space and Structures, 1972). The idea was expressed using the Fresnel diagram:

The argument was pursued using a comparison of three simplified building forms that are like Mae’s stereotypes though without historicist trappings: the pavilion (tower), street and perimeter blocks. Common parameters included building depth, storey height and ‘cut-off angle’ i.e. the line joining the base of one building facade to the top of the facade opposite. Out of this came an idea of the densest or most efficient use of a site the area of which has to increase to keep the angle constant as the number of storeys goes up. Efficiency means the highest ratio of total floor area to site area given the constraints. Among those, the cut-off angle was perhaps the most important. Surprisingly the tower is at its densest with just four storeys much less than the courtyard:

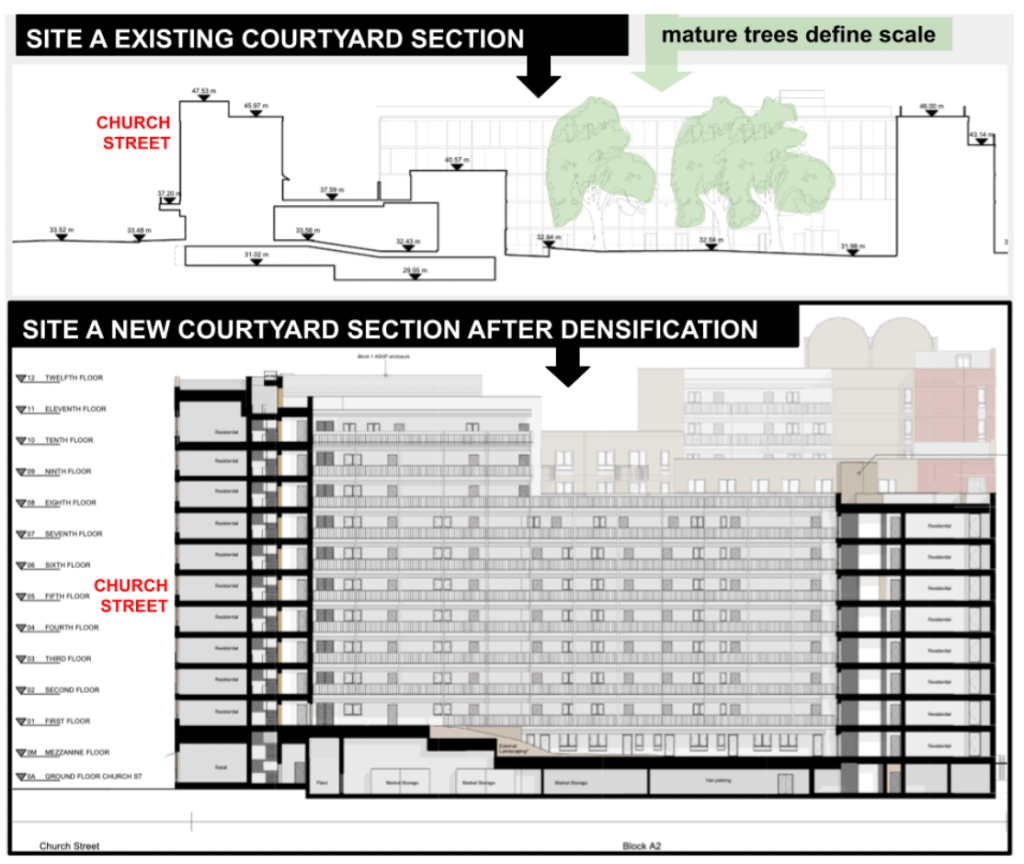

AHMM’s three courtyard blocks – A2, B1 and C1 – arranged along Grafton Road contain 82, 129 and 156 flats respectively. B1 and C1 are the same size as a 25 storey tower block. The equivalence is evidence that a courtyard block can match the density of a tower, as March and Martin argued, but at what cost?

It is far from clear that AHMM’s courtyards are properly daylit. The daylighting report submitted with the planning application by Camden itself is too willing to argue WKTE is ‘urban’ and should therefore put up with below par conditions e.g “The outcome of the contextual study demonstrates that courtyard amenity spaces are inherently challenged within an urban location.” Plainly, this begs the question why WKTE’s masterplanners are so committed to a courtyard layout given the likely impacts on the amenity of the internal courtyard spaces that are so important for the inhabitants – a question which is not answered at all by conservation gush.

The proportions of the courtyards look sure to stop most direct sunshine, bearing in mind the sun only gets above 45° for four months of the year in the UK. The courtyard proportions are restricted by a site layout consisting of badly sized plots where “the balance between plot, building and street” (Lionel March & Leslie Martin)has been lost.

Shortchanging courtyard open space, sunlight penetration and even internal daylighting is self-defeating. The DC’s injunction that “Microclimate conditions must be accounted for in the layout of the communal space” is yet more sheepish post-rationalisation. The whole thing is at odds with the good urban planning Martin and March advanced.

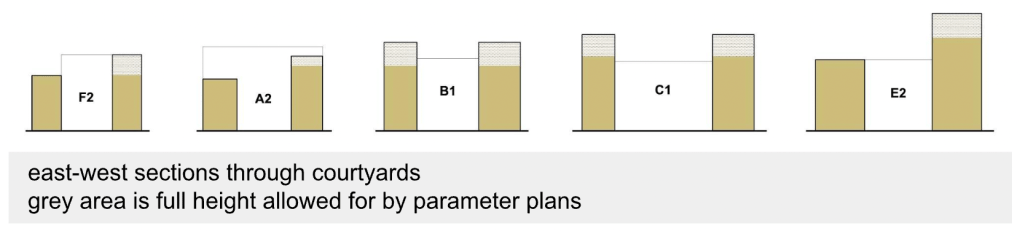

above: extract from AHMM’s Design and Access Statement for WKTE

We are told the courtyard buildings have not got to detailed design stage but in the Daylight, Sunlight and Overshadowing report we find images showing well-developed computer models. The light study model means sections through the courtyard buildings must be available. The difficulty is surely that the sections expose a design that is bad in principle.

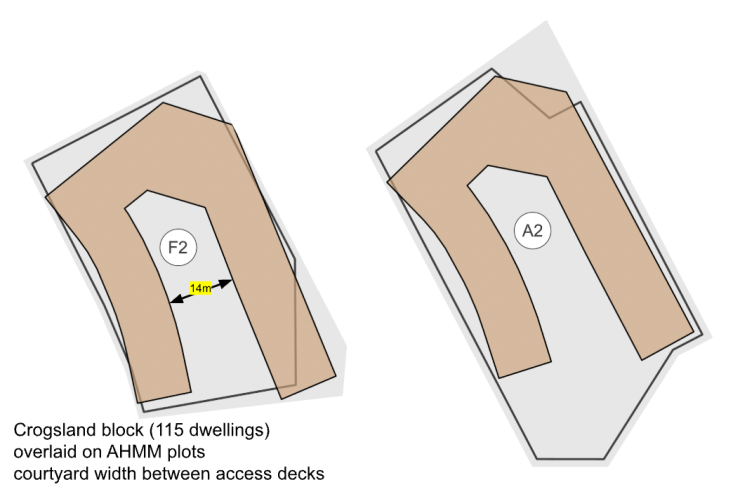

The built-out courtyard scheme on nearby Crogsland Road gives an idea of the sort of spaces AHMM’s WKTE scheme will result in.

above: nearby Crosgland Road development by AHMM

Martin and March considered improved planning meant not “building higher, but …(amalgamating small plots into larger blocks), which allows for lower, more efficient forms like courtyards that preserve open space and daylight”. The courtyard photos of the Crogsland Road scheme show a courtyard which is around 14 metres across (deck to deck) and 17m across (wall to wall). The comparison below suggests the poor precedent set by the Crogsland courtyard should give pause for thought at WKTE.

AHMM’s quasi-picturesque approach avoids the challenge of designing a type. Instead, they have stylised containers big enough to pour the requisite number of flats into at a later date. The Design Code hardly ensures this will work out well; its specification of courtyard space is sketchy to say the least. Far more control over the future could have been achieved through the development of a consistent dwelling/building/city-block pattern based on a sensible social brief. This echoes concerns expressed in the 60s and 70s about the crudeness of debate about density. “Many of the established uses of density lack spatial precision and are unsatisfactory for describing and prescribing urban form” (Meta Berghauser Pont and Per Haupt, The relation between urban form and density, 2007). The parameter plan plus design code approach to the town planning hurdle is “unsatisfactory for describing and prescribing urban form”.

FOR WHOM?

There is much more to be said about the WKTE development. One thing is puzzling: why a progressive council like Camden, with its myriad commitments to ‘knowledge’ and embedding in the ‘Knowledge Quarter’, lacks a more sociologically informed brief for its large housing developments. Developers in the private sector have one, albeit built around market research and comms based on flattering the consumer with status goods.

Abercrombie himself remarked in a 1945 public information film about replanning London that “it’s that loyalty and neighbourliness which holds a group of people together because they have the same interests and pleasures and because they share their troubles and their triumphs”. For two decades, Suzi Hall at the LSE and others like her based in the borough have worked on adjacent questions but are overlooked by town hall.

OUTSIDE TRADITION

A clearly demoralised design team has been overwhelmed by the challenge of WKTE’s redevelopment and is resorting to all manner of excuses to explain poor performance. I am struck by the discord between the claim the WKTE project is ‘landscape-led‘ and committing so much of the site to poor quality courtyard space on the basis that the scheme is ‘urban‘.

AHMM’s courtyard buildings have no pedigree. They are not part of a positive tradition of courtyard urbanism e.g. Cerdà’s original courtyard blocks for the Barcelona Eixample. Their ‘courtyards’ are sad contraptions lying outside the realm of architecture and urbanism, reflecting the disarray of a mediocre design team in the face of an impossible brief. The brief is a symptom of town planning failure and the dissociation of political economy from neighbourhood life.

All over London, there are many poorer developments than WKTE recently built and in progress. Some combine high-rise with courtyard configurations to produce grotesquely anachronistic housing forms recalling 19th Peabody configurations and worse.

above: the Arches development in Lisson Grove (builder Mount Anvil, architects Bell Philips & Mae )

Perversely, where wealth is general, deformed and congested forms might be sustainable – e.g. better off apartment blocks in New York or Paris – but where the relationship between home and neighbourhood is much less exceptional, the new approach to mass housing seems certain to deliver immiseration through quick degradation.

THE HOME

Camden’s Golden Age architects (which have made Gospel Oak internationally famous for housing design) were focused on innovating the dwelling itself. Dwellings, in their hands, were rigid types so assembling them into buildings was exacting although their aims were resolutely modest: to “return to housing the traditional quality of continuous background stuff, anonymous, cellular, repetitive, that has always been its virtue”.

The Golden Age architects were as motivated as AHMM and Mae to learn the lessons of the city but they understood the city emerged from systems e.g. the dwelling/building/city-block pattern rather than ad hoc or appliqué urban design. Their admiration for terraced housing was not expressed in conservation-speak but in systematic, exploratory urbanism.